Archive for the ‘JavaScript’ Tag

JavaScript Dates

new Date() is a JavaScript object containing a number that represents milliseconds since 1/1/1970 UTC. Also defined as the number of milliseconds that have elapsed since the ECMAScript epoch (equivalent to the UNIX epoch) of 1/1/1970.

Interesting Note:

A number in ECMAScript can represent all integers from -9,007,199,254,740,992 to 9,007,199,254,740,992. The time value is something less than that: -8,640,000,000,000,000 to 8,640,000,000,000,000 milliseconds. This works out to approximately -273,790 to 273,790 years relative to 1970. (Reference 21.4.1.1 ECMAScript).

Keep in mind: the month is zero based. All others are 1 based. Example:

let date = new Date(2022,3,29,14,1,30,50);

The integer “3” for the month parameter is not March, but April.

Getters return the time zone of the machine the code is running on. There is the UTC version of the date getters.

JavaScript Prototypes and Inheritance

Function Prototypes and Object Prototypes.

A function’s prototype is the object instance that will become the prototype for all objects created using this function as a constructor.

When a function is created, there is an object created in memory and is connected to the function behind the scenes. Each time an object instance is created using that constructor function, the “.__proto__” prototype for each of the objects point to the same object in memory for the constructor function prototype.

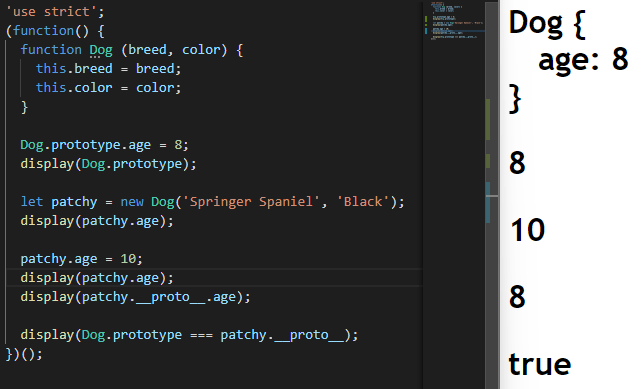

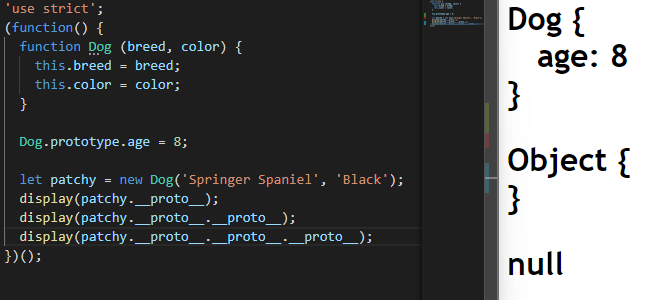

Let’s update the Dog prototype and add an age property:

The “patchy” instance age automatically updates. To further demonstrate that the function prototype object is the same across all instances, let us update the .__proto__ age value on the patchy instance:

So far, these are the prototype properties. What would happen if we updated the age property (not the __proto__.age) on the patchy instance?

“patchy.age” is an instance property, not a prototype property. JavaScript will examine the object and see if it has an age property. In the first display(patchy.age), the instance does not have an age property. JavaScript then examines the object prototype for an age property. In this case patchy.__proto__ has an age property with a value of 8. After we updated the patchy.age property to 10, what really happened, is we added an instance property of age, to the patchy object. In the second display(patchy.age), JavaScript checks the object instance for an age property. It finds one and displays its value of 10. We can see, the patchy instance has access to both its own “age” property, and it’s __proto__ “age” property.

Using the “hasOwnProperty” we can further look into this.

An object’s prototype is the object instance from which the object is inherited.

In the previous examples, the “patchy” has been inheriting from the Dog prototype object. The prototype is also inheriting from the Object prototype. There are multiple levels of inheritance at work. The inheritance chains can be shown as follows:

The following code demonstrates how to put inheritance chains to work so our objects can inherit prototype properties from other objects:

'use strict';

(function() {

function Person (firstName, lastName, age) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.age = age;

Object.defineProperty(this, 'fullName', {

get: function() {

return this.firstName + ' ' + this.lastName

},

enumerable: true

});

}

function Student(firstName, lastName, age) {

Person.call(this, firstName, lastName, age);

this._enrolledCourses = [];

this.enroll = function(courseId) {

this._enrolledCourses.push(courseId);

};

this.getCourses = function() {

return this.fullName + ' is enrolled in: ' +

this._enrolledCourses.join(', ');

};

}

Student.prototype = Object.create(Person.prototype);

Student.prototype.constructor = Student;

let homer = new Student('Homer', 'Simpson', 45);

homer.enroll('CS301');

homer.enroll('EN101');

homer.enroll('CH101');

display(homer.getCourses());

display(Student.prototype.constructor);

})();

Babylon JS

Can’t say I was impressed. I understand it is in JS and WebGL what Flash is to the browser. Not bad though for smaller, simpler animated projects.

Of the 3 examples on their site (http://www.babylonjs.com), Mansion did not run, Dino hunt was OK, but poorly designed (not Babylon’s fault!), Retail, lagged and would not work at times. I accessed them using Safari Version 8.0 (10600.1.25) on Mac OS X Yosemite 10.10, Intel Graphics Iris 1536 MB.

Looks like it still needs some work.

I believe the potential here is great as an alternative to Flash for new developers. However, when one considers the large established base of Flash developers, IMHO, it will be on the scale of years before we see wide-scale use. At best, for smaller animated projects, it’s not bad (like the Dino Hunt).

I’ll have to re-visit in a year and compare what I see then, with what I’ve written here. Reminder set.

Simple “Hello World” Javascript Test Driven Development (TDD) Example Using QUnit

I’ve been meaning to try out Javascript TDD. So, here goes.

Premise: We want to develop a simple Javascript object that will contain an ID and a Title. When developed, we will use it in our web page Index.html.

- Download QUnit from: http://qunitjs.com

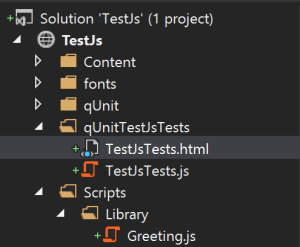

- I placed the unit testing artifacts in their own folder.

- The bare minimum needed by QUnit in the TestJsTests.html file:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8" /> <title>Javascript Unit Testing Using QUnit</title> <link href="../qUnit/qunit-1.17.1.css" rel="stylesheet" /> </head> <body> <div id="qunit"></div> <div id="qunit-fixture"></div> <script src="../qUnit/qunit-1.17.1.js"></script> <script src="TestJsTests.js"></script> </body> </html> - Time to setup the test we know will fail. Adding code to TestJsTests.js. The idea is to define a class “Greeting” with two properties: “Id”, and “Title”. We will write our initial test, as if the class with these properties exists.

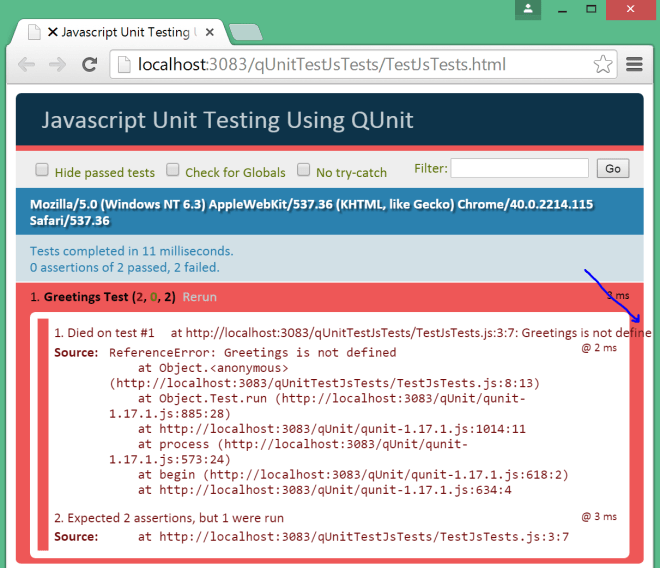

/// <reference path="../qUnit/qunit-1.17.1.js" /> /* globals QUnit, Greeting */ QUnit.test('Greeting Test', function(assert) { 'use strict'; assert.expect(2); var x = Greeting(1, 'Hello World'); assert.ok(x.Id === 1, 'Id property passed!'); assert.deepEqual(x.Title, 'Hello World', 'Title property passed!'); }); - As expected, the tests fail. (Note: there seems to be a layout bug in QUnit as we have a bit of runoff indicated by the blue arrow). This is good, we want it to fail so we can have a developer write the barest of minimum Javascript code needed to make the unit tests pass.

- Proceeding with developing Greeting.js.

- Code for Greeting.js.

/* exported Greeting */ var Greeting = (function () { 'use strict'; var p = function (id, title) { this.Id = id; this.Title = title; }; return p; })(); - Updating the TestJsTests.html to include the Greeting.js code.

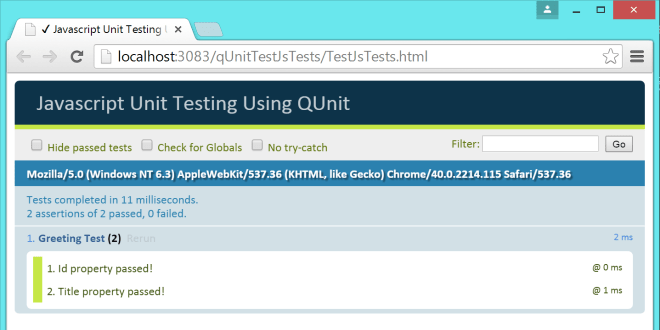

<body> <div id="qunit"></div> <div id="qunit-fixture"></div> <script src="../qUnit/qunit-1.17.1.js"></script> <script src="../Scripts/Library/Greeting.js"></script> <script src="TestJsTests.js"></script> </body> - And the unit tests pass!

- In conclusion, we can now be confident that the code developed in Greeting.js is indeed good. With available unit test for our JS code, we can also confidently refactor our code. As the scope of the project grows, we can expand further on the behaviors expected of the code by writing further tests asserting the expected behavior. This can be valuable to the developers, as they can confidently develop code that causes the unit tests to pass.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment